Nel Medioevo le erbe hanno costituito una delle forme principali della medicina. Gran parte dello studio delle erbe medicinali avveniva, oltre che nelle università, nei monasteri. E’ infatti grazie alla tradizione monastica che ci sono arrivati diversi erbari con i quali siamo potuti risalire alle conoscenze nel campo della botanica e della medicina del tempo.

La medicina monastica ebbe le sue origini nella nuova Regola, redatta da San Benedetto da Norcia nel monastero da lui stesso fondato a Montecassino (529 d.C.). Benedetto prescrisse che all’interno del monastero fosse riservata particolare cura alla trascrizione dei codici antichi, tra cui numerose opere naturalistiche e mediche scritte da autori come Ippocrate, Galeno, Catone (De agricoltura), Plinio il Vecchio (Naturalis Historia) e Dioscoride (De materia medica). Essi ispirarono i monaci medioevali all’approfondimento dello studio delle piante e dei rimedi da esse ricavati. I monaci inoltre furono spinti alla ricerca e all’applicazione in campo medico delle virtù delle piante in quanto avevamo il dovere morale, in particolare i monaci infirmarii, di accogliere i poveri, i mendicanti e i malati e di dedicarsi alla loro cura. Da queste esigenze nacque l’Hortus medicus o Hortus simplicium, l’orto delle cosiddette “semplici”, ovvero delle erbe medicali. Accanto a questo si trovava l’Hortus conclusus che racchiudeva invece alberi da frutto, fiori, fontane e ruscelli. L‘Hortus simplicium era allestito in un’area specifica del monastero, solitamente accanto all’infermeria e destinato alla coltivazione delle piante da cui venivano estratti, con differenti procedimenti, i medicamenti. La cura non agiva solo sul corpo, ma anche sull’anima. L’Hortus doveva essere ben delimitato e separato dagli altri spazi verdi in segno di distinzione: era il luogo di pace e di silenzio per eccellenza, di perfetta armonia tra natura e cultura.

Probabilmente le specie botaniche più presenti in essi erano: salvia, basilico, menta, iris, anice, melissa, lavanda, rosmarino, valeriana, liquirizia, aloe e papavero. Queste erbe una volta essiccate venivano conservate nell’ armarium pigmentariorum, un armadio dalla robusta struttura, chiuso in modo tale da non lasciar filtrare troppo arie né luce, per mantenere inalterate le loro proprietà terapeutiche. Esse venivano poi conservate in decotti e sciroppi. Fu proprio questa attività di cura e di produzione di farmaci a trasformare la medicina da opera pia in disciplina.

Probabilmente le specie botaniche più presenti in essi erano: salvia, basilico, menta, iris, anice, melissa, lavanda, rosmarino, valeriana, liquirizia, aloe e papavero. Queste erbe una volta essiccate venivano conservate nell’ armarium pigmentariorum, un armadio dalla robusta struttura, chiuso in modo tale da non lasciar filtrare troppo arie né luce, per mantenere inalterate le loro proprietà terapeutiche. Esse venivano poi conservate in decotti e sciroppi. Fu proprio questa attività di cura e di produzione di farmaci a trasformare la medicina da opera pia in disciplina.

Nel XII secolo la badessa di un monastero benedettino tedesco Ildegarda Von Bigen scrisse nel XII il Liber Simplicis Medicinae, uno dei più importanti trattati di erboristeria e storia naturale. In esso raccomandava la mentuccia per esempio la mentuccia per la cefalea e il mal di stomaco, il cumino per la nausea, il tanaceto per la tosse il raffreddore, l’achillea per le emorragie, ancora oggi impiegate per tali scopi.

La medicina fu la prima disciplina scientifica a uscire dalle abbazie e dai monasteri. Risale al IX secolo la Scuola Medica Salernitana che è stata la prima istituzione medica d’Europa, considerata come l’antesignana delle moderne università. La leggenda racconta che la Scuola fu fondata da quattro maestri, Elino, Ponto, Adela e Salerno, che insegnavano rispettivamente in ebraico, in greco, in arabo e in latino. Questo ci fa capire la grande apertura culturale di questa scuola in cui Greci e Latini, Arabi ed Ebrei, monaci e laici, operarono fianco a fianco fondendo le correnti mediche dell’antichità.

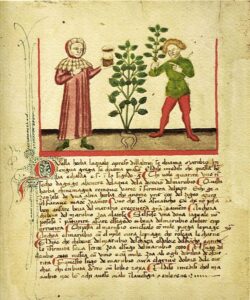

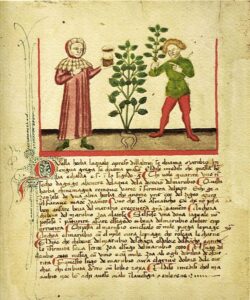

Erbario della Scuola Medica Salernitana

In questa realtà culturale operarono molte donne, non solo come allieve, ma anche come insegnanti. La più famosa di tutte fu Trotula, nata a Salerno dalla nobile famiglia De Ruggiero, attiva intorno al 1050. E’ autrice di due opere: De ornatu mulierum e De passionibus mulierum ante, in et post partum. Il primo è un trattato di cosmesi in cui vengono forniti alle donne consigli per conservare e accrescere la propria bellezza. Il secondo è un vero e proprio manuale di ostetricia, ginecologia e puericultura. Ella ricorre alla medicina delle piante e delle erbe, somministrate in tutte le forme possibili, dall’impiastro al decotto, dall’olio al succo, dai bagni ai suffumigi. I principi fondamentali della dottrina di Trotula erano talvolta molto semplici. Eccone un esempio:

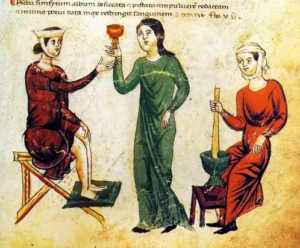

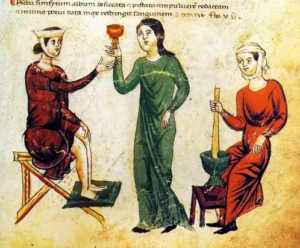

Trotula e le mulieres Salernitanae

“Se il parto si presenterà difficile, prima di tutto bisogna appellarsi all’aiuto di Dio. Poi, passando ai rimedi umani, a una donna che incontra difficoltà nel parto giovano i bagni in acqua dove siano stati cotti malva, fieno greco, semi di lino e orzo. Le si ungano i fianchi, il ventre, le cosce e l’inguine con olio di viole e di rose. La si strofini energicamente e le si dia da bere un infuso di acetosella con polvere di menta e una dracma di assenzio. La si faccia sternutire accostandole al naso polvere d’incenso, oppure di candisio, di pepe o di euforbia” (dal capitolo XVIII: il parto difficile).

La notorietà di Trotula al di fuori dell’Italia è testimoniata dal fatto che viene citata da Geoffrey Chaucer nel suo capolavoro, The Canterbury Tales (Wife of Bath’s Prologue, 676-680). La donna di Bath si lamenta che il marito legga un libro misogino in cui si porta ampia documentazione sulla malvagità delle mogli. Trotula è citata in questo testo probabilmente come autrice del De ornatu mulierum i cui consigli per valorizzare artificialmente la bellezza delle donne potevano apparire come manifestazione dell’astuzia e falsità femminile.

Ecco un elenco di alcune delle erbe più utilizzate nell’antichità di cui si largo uso ancora oggi:

- Timo – Thymus

Il timo, dal greco thymòs, indicava il principio della vitalità, il respiro, il cuore, che secondo i Greci era sede delle passioni: l’ira, il coraggio e l’ardore. Esso ha proprietà antisettiche e balsamiche per le vie respiratorie, infatti è molto utile nelle affezioni come laringite, bronchite e asma. Inoltre tonifica il sistema nervoso ed è indicato in caso di esaurimento sia fisico che psichico. Nel Medioevo le nobildonne erano solite ricamare un’ape sui fiori di timo sulle insegne dei loro cavalieri, come auspicio di buona sorte in battaglia. Un rametto della pianta veniva spesso messo sotto i cuscini in quanto si riteneva potesse facilitare il sonno e allontanare gli incubi. In quest’epoca i rami di timo venivano bruciati come l’incenso per facilitare il passaggio alla nuova vita del defunto e l’odore che sprigionava bruciandolo era utile ad allontanare vermi, serpenti e animali velenosi. E’ anche uno degli ingredienti dell’aceto dei quattro ladri. Nel 1630 infatti, durante la peste, vennero catturati dei ladri che derubavano i cadaveri. Il giudice volle sapere come facessero a non contagiarsi ed essi rivelarono il loro segreto in cambio della libertà. Diedero la ricetta di questo aceto, con cui si spalmavano il corpo, un macerato di varie erbe fra cui salvia, rosmarino, timo e lavanda.

- Lavanda – Lavandula

Lavanda deriva dal verbo latino lavare e si rifà all’usanza di utilizzare la pianta per l’igiene e la bellezza personale. Nel Medioevo la Scuola Salernitana la consigliava per la cura della paralisi, mentre Ildegarda proponeva il vino di lavanda oltre che per i problemi al fegato e ai polmoni anche per assicurare “all’uomo una pura scienza e una sana intelligenza”. La lavanda per le sue proprietà sedative poteva essere utilizzata in caso di nervosismo, tensione e ansia, ma è anche molto efficace, sotto forma di olio o di essenza, per calmare dolori articolari e muscolari.

- Melissa – Melissa officinalis

Il nome Melissa deriva dal latino Melissophillum che a sua volta deriva dal greco Mélisse (ape) e Phyllon (erba), quindi erba gradita alle api. Questa pianta sembrava capace di curare molti disturbi quali coliche, indigestione, cefalee, artriti, mal di denti e piaghe. Era inoltre indicata nei casi di ansia, insonnia e stress. Applicata esternamente disinfetta le ferite promuovendone la cicatrizzazione.

- Camomilla – Matricaria chamomilla

Il nome deriva dal greco khamaìmelon che significa mela del terreno per l’odore che somiglia a quello della mela renetta. Nel Medioevo veniva bruciata per allontanare le infezioni della peste e di altre malattie infettive. C’era anche l’usanza di appendere ciuffi di camomilla sulle culle dei neonati per conservarli da possibili malattie epidemiche. Per le sue qualità sedative, antispasmodiche e digestive era consigliata nei casi di insonnia e nervosismo.

- Salvia – Salvia Officinalis

Il suo nome deriva dal latino Salvus (salvo). Per la scuola medica Salernitana l’erba era ritenuta miracolosa perché confortava i nervi, funzionava come antidoto negli avvelenamenti, guariva dalla paralisi e assicurava all’uomo una lunga e serena vecchiaia. Per questo le è stato attribuito anche il nome Salvia Salvatrix (salvia che salva) che ha cognato la famosa frase “Cur moriatur homo, cui salvia crescit in horto?” – “Perché mai deve morire l’uomo a cui cresce la salvia nell’orto?”. Questa pianta è un’efficace rimedio per molte affezioni ginecologiche ed è digestiva e antisettica. Inoltre tonifica il sistema nervoso ed è perciò utile negli stati di depressione, astenia, ipotensione e vertigini. L’essenza di salvia in dosi elevate è tossica.

- Iperico – Hypericum perforatum

Questa pianta era una delle più utilizzate per i problemi nervosi e un rimedio popolare per la pazzia. Nel Medioevo era inoltre apprezzata per la sua proprietà cicatrizzante. Durante le crociate i Ospedalieri di San Giovanni, cavalieri monaci, la usavano durante le crociate per risanare le ferite e la portavano sempre con sé probabilmente sotto forma di olio. La pianta era inoltre nota per le sue proprietà antisettiche, antinfiammatorie, antidepressive e depurative.

Durante il Medioevo centinaia di monaci e laici hanno coltivato, studiato e sperimentato un’infinità di piante, ponendo le basi della medicina moderna. Questa ha sviluppato metodi più scientifici, ma ha sempre mantenuto uno stretto legame con la terapia delle erbe medicinali.

MEDICINAL HERBS IN THE MIDDLE AGES

In the Middle Ages, herbs were one of the main forms of medicine. Most of the study of medicinal herbs took place, as weel as in university, in monasteries. It is in fact thanks to the monastic tradition that several herbaria have arrived; with them we were able to trace the knolwledge in the field of botany and medicine of that time.

Monastic medicine had its origins in the new Rule, drown up by St.Benedict of Norcia in the monastery he himself founded in Montecassino (529 AD). Benedict prescribed that in the monastery particular care was given to the transcription of ancient codices, including numerous naturalistic and medical works written by authors such as Hippocrates, Galen, Cato (De Agricoltura), Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia) and Dioscorides (De Materia Medica). They inspired medival monks to deepen the study of plants and the remedies derived from them. The monks were also encouraged to research and apply the virtues of plants in the medical field becausethey had the moral duty, in particular the infirmarii monks, to welcome the poor, beggars and the sick and to devote themselves to their care. From these needs the Hortus medicus was born. It was also named Hortus simplicium, the garden of the so-called “simple” or medicinal herbs. Next to this was the Hortus conclusus which contained fruit trees, flowers, fountains and streams. The Hortus simplicium was set up in a specific area of the monastery, usually next to the infirmary, and intended for the cultivation of the plants from which medicaments were extracted, with different procedures. The treatment acted not only on the body, but also on the soul. The Hortus had to be well delimited and separated from the other green spaces as a sign of distinction: it was the place of peace and silence of perfect harmony between nature and culture.

Probably the most present botanical species in it were: sage, mint, iris, anise, lemon balm, lavender, rosemary, valerian, licorice, aloe and poppy. These herbs, once dried, were stored in the armarium pigmentariorum, a cabinet with a sturdy structure, closed in such a way as not to allow too much air or light to filter, in order to mantain their therapeutic properties unaltered. Then they were preserved in decoctions and syrups. It was precisely this activity of treatment and production of medicaments that transformed medicine from a work of mercy into a discipline.

Probably the most present botanical species in it were: sage, mint, iris, anise, lemon balm, lavender, rosemary, valerian, licorice, aloe and poppy. These herbs, once dried, were stored in the armarium pigmentariorum, a cabinet with a sturdy structure, closed in such a way as not to allow too much air or light to filter, in order to mantain their therapeutic properties unaltered. Then they were preserved in decoctions and syrups. It was precisely this activity of treatment and production of medicaments that transformed medicine from a work of mercy into a discipline.

In the 12th century, the abbes of a German Benedictine monastery, Hildegard Von Bigen, wrote the Liber Simplicis Medicinae, one of the most important treatises on herbal medicine and natural history. In it she recommended, for example, mint for headache and stomach pain, cumin for nausea, tansy for cough and cold, yarrow for bleeding, herbs still used today for these purposes.

Medicine was the first scientific discipline to come out of abbeys and monasteries. Salerno Medical School dates back to the 9th century and was the fisrt medical institution in Europe, considered as the forerunner of modern universities. Legend has it that the School was founded by four masters, Elino, Ponto, Adela and Salerno, who taught respetcively in Hebrew, Greek, Arabic and Latin. This makes us understand the great cultural openness of this school in which Greeks and Latins, Arabs and Jews, monks and laity worked side by side, merging the medical currents of antiquity.  Many women worked in this culural reality, not only as students, but also as teachers. The most famous of all was Trotula, born in Salerno from the noble De Ruggiero family, active around 1050. She is the author of tow works: De onrnatu mulierum and De passionibus mulierum ante, in et post partum. The first one is a cosmetic treatise in which women are given advice on how to preserve and enhance their beauty. The second one is a real manual of obstetrics, gynecology and childcare. She resorts to the medicine of plants and herbs, administered in all possible forms, from poultice to decoction, from oil to juice, from baths to fumigations. The basic principles of Trotula’s doctrine were sometimes very simple. Here is an example:

Many women worked in this culural reality, not only as students, but also as teachers. The most famous of all was Trotula, born in Salerno from the noble De Ruggiero family, active around 1050. She is the author of tow works: De onrnatu mulierum and De passionibus mulierum ante, in et post partum. The first one is a cosmetic treatise in which women are given advice on how to preserve and enhance their beauty. The second one is a real manual of obstetrics, gynecology and childcare. She resorts to the medicine of plants and herbs, administered in all possible forms, from poultice to decoction, from oil to juice, from baths to fumigations. The basic principles of Trotula’s doctrine were sometimes very simple. Here is an example:

“If childbirth turns out to be difficult, first of all one must appeal to God’s help. Then, moving on to human remedies, a woman who has difficulties in childbirth benefits baths in water where mauve, fenugreek, flax seeds and barley have been cooked. Grease her hips, belly, thighs and groin with oil of violets and roses. Rub it vigorously and give her an infusion of sorrel with mint powder and a drachma of absinthe. Make her sneeze by putting incense powder, or candisio, pepper or euphorbia powder close to her nose (from chapter XVIII: difficult childbirth).

Trotula’s notoriety outside Italy is evidenced by the fact that she is mentioned by Geoffry Chaucer in his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales (Wife of Bath’s Prologue, 676-680). The Wife of Bath complains that her husband is reading a misogynistic book that brings extensive documenation on the wickedness of wives. Trotula is mentioned in this text probably as the author of the De Ornatu mulierum whose advice for artificially enhancng the beauty of women could appear as a manifestation of feminine cunning and falsity.

Here is a list of some of the herbs most used in antiquity that are still widely used today:

- Thyme – Thymus

Thyme, from the Greek thymòs, indicated the principle of vitality, breath, heart, which, according to the Greeks, was the seat of passions such as anger, courage and ardor. It has antiseptic and balsamic properties for the respiratory tract; in fact it is very useful in diseases, such as laryngitis, bronchitis, and asthma. It also tones the nervous system and is indicated for both physical and mental exhaustion. In the Middle Ages, noblewomen used to embroider a bee on thyme flowers on the insignia of their knights as a wish for good luck in battle. A spring of this plant was often placed under pillows as it was believed to facilitate sleep and ward off nightmares. At this time the thyme branches were burned like incense to facilitate the passage to the new life of the deceased and the smell that was released by burning them was considered useful to remove worms, snakes and poisonous animals. Thyme is also one of the ingredients of “the vinegar of the four thieves”. In fact, in 1630, during the plague, some thieves were caught while robbing corpses. The judge wanted to know how they did not get infected and they revealed their secret in exchange for freedom. They gave the recipe for this vinegar with which they spread their bodies, a macerated of various herbs including sage, rosemary, thyme and lavender.

Lavender – Lavandula

Lavender derives from the Latin verb lavare and refers to the custom of using the plant for hygiene and personal beauty. In the Middle Ages the Salerno Medical School recommended it for the treatment of paralysis, while Hildegard proposed lavender wine, for liver and lung problems, as well as to ensure “pure sience and healthy intelligence for man”. For its sedative properties lavender can be used in case of nervousness, tension and anxiety, but is also very effective, in the form of oil or essence, to soothe joint and muscle pain.

- Lemon balm – Melissa officinalis

The name Melissa derives from the Latin Melissophillum which in turn derives from the Greek Mélisse – bee and Phyllon – herb, therefore a herb appreciated by bees. This plant seemed capable of curing many ailments such as colic, indigestion, headaches, arthritis, toothache and sores. It was also indicated in cases of anxiety, insomnia and stress. Applied externally, it disinfects wounds, promoting their healing.

- Chamomile – Matricaria Chamomilla

The name derives from the Greek Khamaìmelon which means apple of the soil, due to the smell which is similar to that of the rennet apple. In the Middle Ages it was burned to ward off infections from various infectious diseases and the plague. There was also the custome of hanging tufts of chamomile on the cradles of babies to protect them from possible epidemic diseases. For its sedative, antispasmodic and digestive qualities it is recommended in cases of insomnia and nervousness.

- Sage – Salvia Officinalis

It’s name derives from the Latin Salvus. For the Salerno Medical School, the herb was considered miraculous because it comforted the nerves, worked as an antidote to poisonings, healed from paralysis and ensured man a long and peaceful old age. For this reason it was also given the name Salvia Salvatrix (sage that saves), hence the famous phrase “Cur moriatur homo, cui salvia crescit in horto?” (“Why must the man who grows sage in the garden die?”). This plant is an effective remedy for many gynecological ailments and is digestive and antiseptic. It also tones the nervous system and is therefore useful in states of depression, asthenia, hypotension, and dizziness. Sage essence in high doses is toxic.

- Hypericum – Hypericum perforatum

This plant was one of the most used for nerve problems and was a popular remedy for insanity. In the Middle Ages it was also appreciated for its healing properties. During the Crusades, the Hospitallers of San Giovanni, monk nights, used it to heal wounds and always carried it with them, probably in the form of oil. The plant was also known for its antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant and purifying properties.

During the Middle Ages, hundreds of monks and lay people cultivated, studied and experimented with an infinite number of plants, laying the foundations for modern medicine. This has developed more scientific methods, but has always maintained a close link with the therapy of medicinal herbs.

Sitografia:

http://giardinonaiadi.blogspot.com/2013/12/hortus-simplicium-orti-monastici.html

https://www.bluedragon.it/medioevo/medicina.htm

http://www.moreianuensis.net/tag/erbe/

https://www.giardinosemplici.it/hortus-simplicium

Bibliografia:

Ferruccio Bertini, F. Cardini, C. Leonardi, M.T. Fumagalli Beonio Brocchieri, Il medioevo al femminile, Trotula, il medico di F. Bertini, Bari, editori Laterza, 1989

ARTICOLO REDATTO DA SOFIA MAGGIA DELLA CLASSE III A DEL LICEO CLASSICO

Commenti recenti