CONSULTA LINK

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/12-things-you-didnt-know-about-women-in-the-first-world-war

HISTORIC UK

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-One-Women-at-

Ancora oggi, spesso, lo studio degli eventi storici relativi al primo conflitto mondiale ci trasmette un’idea della guerra come di un universo tutto maschile, in cui rivestono un ruolo centrale i soldati, le battaglie, le decisioni dei grandi generali e la vita di trincea. Eppure, anche le donne, pur non combattendo in prima persona, diedero un apporto fondamentale allo sforzo bellico. Ciò contribuì a modificare il loro ruolo nella società e a dare una spinta decisiva al processo di emancipazione femminile.

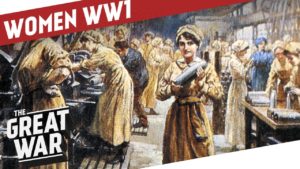

Le donne furono chiamate ad affiancare e in molti casi anche a sostituire gli uomini in una vasta gamma di occupazioni: moltissime vennero impiegate nell’industria bellica, le crocerossine fornirono assistenza ai soldati, altre confezionavano da casa indumenti da inviare al fronte. Lavorarono come braccianti agricole, cuoche, medici, telegrafiste, dattilografe, macchiniste e poliziotte, continuando nello stesso tempo a svolgere le mansioni domestiche.

Fu una vera e propria rivoluzione quella che si verificò nelle relazioni fra generi, in una società in cui il lavoro delle donne (soprattutto quelle di classe agiata) costituiva ancora un’eccezione. Grazie alla guerra furono messi in discussione modelli di comportamento fino ad allora ritenuti immutabili e gerarchie e distinzioni che sembravano ormai fortemente consolidate.

Già da prima della guerra, in tutta Europa venivano condotte campagne per far ottenere alle donne i diritti completi di cittadinanza, le cosiddette “suffragette”. Quando la crisi internazionale cominciò a dispiegarsi fra il giugno e il luglio del 1914, le donne erano ancora quasi ovunque prive del diritto di voto e non avevano possibilità di pronunciarsi sulle questioni politiche.

Furono rare le voci femminili che si fecero sentire nel criticare pubblicamente i governi a guerra dichiarata. Fra queste, le italiane Linda Malnati e Carlotta Clerici, che collaborarono nel 1914 al “Comitato pro umanità”

Lo scoppio della guerra rappresentò un passo molto significativo verso l’indipendenza della donna; con la partenza degli uomini per il fronte, alla donna spettava il compito di allevare da sola i figli e di prendersi cura dell’abitazione, ma soprattutto di sostituire gli uomini in tutte quelle attività che fino ad allora erano state prerogativa esclusivamente maschile.

Oltre al lavoro, si impegnavano in attività di beneficenza e assistenza ai soldati, in organizzazioni volontarie di soccorso e nella cura di feriti e ammalati.

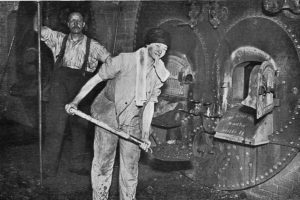

Le lavoratrici e le donne più povere della classe media erano addette ai lavori più faticosi. Nel settore industriale e commerciale esse lavoravano in condizioni spaventose, a causa dell’abrogazione del riposo domenicale, del mancato pagamento degli straordinari e dell’aumento delle ore di lavoro fino a tredici giornaliere: fattori che moltiplicarono gli incidenti, le malattie e gli aborti spontanei.

La manipolazione di sostanze chimiche velenose provocò spesso problemi di salute a molte donne; inoltre, le fabbriche e i depositi di esplosivi erano a costante rischio di incidenti.

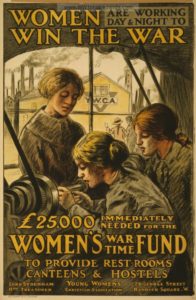

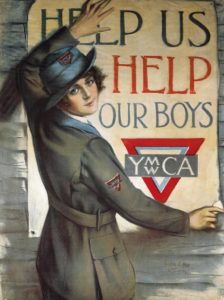

Con il progredire del conflitto, le amministrazioni militari si trovarono di fronte a nuovi impegni ed esigenze che riguardavano sia i problemi sociali sia gli equipaggiamenti dei soldati, e furono costrette a richiedere l’aiuto volontario dei cittadini. Aristocratiche e borghesi realizzavano gratuitamente lavori di cucito e a maglia per scopi patriottici e di beneficenza. Le diverse associazioni femminili si impegnarono nella raccolta di fondi e donazioni e anche nel trovare lavoro per le donne disoccupate. Una fra le più importanti di queste associazioni fu il Corpo militare ausiliario femminile, creato nel 1917 nel Regno Unito; alla fine della guerra ne facevano parte 57.000 donne.

Numerose intellettuali rievocarono nei loro scritti la condizione delle donne durante la guerra. In particolare, a Trieste visse a quell’epoca una generazione di giovani donne accomunate da un’ardente fede patriottica e una rigorosa formazione culturale che emergono chiaramente dalle loro lettere, i loro romanzi e i loro diari. Fra queste c’è Elody Oblath Stuparich.

In alcune donne l’entusiasmo per la guerra fu così grande che vollero partecipare ai combattimenti fingendo di essere uomini. In Italia donne come Luigia Ciappi di Firenze e Gioconda Sirelli di Milano, cercarono di arrivare al fronte vestite da soldato, ma vennero subito identificate e rimandate a casa. In Austria-Ungheria ragazze e donne furono impegnate al fronte su base volontaria per attraversare di nascosto le linee nemiche e raccogliere informazioni. Molte furono impiegate come portatrici e lavoratrici militarizzate.

Fra le figure di donna che combatterono in prima persona va ricordata Flora Sandes,

Fu la prima donna ad essere nominata ufficiale dell’esercito serbo e la prima donna inglese a essere ufficialmente reclutata come soldato.

Molte furono anche le donne che, per motivazioni diverse (bisogno di denaro, intenti patriottici o ricerca di avventura), prestarono il loro servizio come spie.

La guerra provocò inoltre grandi cambiamenti nella moda femminile. Con l’ingresso delle donne nelle fabbriche, le gonne lunghe e strette di quegli anni, piuttosto fastidiose nel lavoro quotidiano, lasciarono il posto a modelli più corti e comodi. I colori degli abiti assunsero maggiore uniformità, abbandonando le sfarzose fantasie degli anni precedenti in nome del rigore della guerra. Anche le pettinature diventarono più sbrigative, con capelli tirati indietro e tagliati più corti. Sul finire della guerra, la moda cercò di restituire una nuova eleganza alle donne lavoratrici, ma senza perdere il carattere di praticità che gli abiti avevano assunto negli ultimi anni.

La fine della guerra portò ad un ridimensionamento degli eserciti e indirizzò l’industria verso prodotti rispondenti alle nuove esigenze di un mercato esclusivamente civile. I posti di lavoro diminuirono e le prime ad essere licenziate furono le donne. Coloro che si trovarono nella situazione più difficile, furono le vedove e le mogli degli invalidi di guerra: per queste la perdita di un’occupazione rappresentò un evento drammatico perché, in mancanza di un marito che fosse in grado di lavorare, riuscire a sostenere la famiglia diventava particolarmente difficoltoso.

In ogni caso, per le donne un ritorno alla situazione dell’anteguerra era impossibile perché, almeno nei Paesi democratici, con il raggiungimento dell’indipendenza economica e politica, esse avevano trovato una nuova dimensione nella società da cui non era più possibile tornare indietro.

Women during the First World War

Even today, often, the study of historical transmits events related to the First World War an idea of war as an all-male universe, in which the soldiers, the battles, the decisions of the great generals and the life of trench play a main role. Yet even women, though not fighting in person, gave a essential contribution to the war effort. This helped to change their role in society and to give a decisive push to the process of female emancipation.

Women were called to assist and in many cases also to replace the in a wide range of occupations: many were employed in the war industry, nurses provided assistance to the soldiers, others made clothes to be sent from home to the front. They worked as agricultural laborers, cooks, doctors, telegraphists, typists, machinists and policemen, while continuing to perform the household tasks.

It was a real revolution that occurred in the relations between genres, in a society in which the work of women (especially those of wealthy class) was still an exception. Thanks to the war, behavior models hitherto considered immutable, hierarchies and distinctions that seemed to be strongly consolidated were questioned.

Already before the war, campaigns were conducted across Europe to get women the full rights of citizenship, the so-called “suffragettes”. When the international crisis began to unfold between June and July 1914, women were still almost everywhere without the right to vote and had no chance to comment on political issues.

The female voices that made themselves heard in publicly criticizing the declared war governments were rare. Among these, the Italian Linda Malnati and Carlotta Clerici, who collaborated in 1914 at the “Pro-Humanity Committee”.

The outbreak of the war represented a very significant step towards the independence of the woman; with the departure of the men for the front, the woman had the task of raising on her own children and taking care of the house, but, above all, to replace the men in all those activities that until then had been exclusively male prerogative.

In addition to work, they put effort in charitable activities and assistance to soldiers, in voluntary relief organizations and in the care of injured and ill people.

The workers and the poorest women in the middle class were charged with the hardest jobs. In the industrial and commercial sector they worked in appalling conditions, due to the abrogation of the Sunday rest, the non-payment of overtime and the increase in working hours to thirteen daily: factors that multiplied accidents, illnesses and spontaneous abortions

The handling of poisonous chemicals often caused health problems for many women; in addition, factories and explosives storages were at constant risk of accidents.

As the conflict progressed, the military administrations found themselves faced with new commitments and demands that affected both the social problems and the equipment of the soldiers, and were forced to request the voluntary help of the citizens. Aristocrats and bourgeois made free sewing and knitting works for patriotic and charitable purposes. The various women’s associations put effort into raising funds and donations and also in finding work for unemployed women. One of the most important of these associations was the Women’s Auxiliary Military Corps, created in 1917 in the United Kingdom; at the end of the war there were 57,000 women.

Many intellectuals recalled the status of women during the war in their writings. In particular, in Trieste at that time a generation of young women united by an ardent patriotic faith and a rigorous cultural formation that clearly emerged from their letters, their novels and their journals. Among these is Elody Oblath Stuparich.

In some women the enthusiasm for the war was so great that they wanted to participate in the fights by pretending to be men. In Italy women like Luigia Ciappi of Florence and Gioconda Sirelli of Milan, tried to get to the front dressed as a soldier, but were immediately identified and sent home. In Austria-Hungary, girls and women were voluntarily engaged in the front to secretly cross enemy lines and gather information. Many were employed as carriers and militarized workers.

Among the female figures who fought in the first person is Flora Sandes,

She was the first woman to be nominated as an officer of the Serbian army and the first English woman to be officially recruited as a soldier.

Many were also women who, for different reasons (need of money, patriotic intent or adventure research), lent their service as spies.

The war also caused big changes in women’s fashion. With the entry of women into the factories, the long and narrow skirts of those years, rather annoying in their daily work, gave way to shorter and more comfortable models. The colors of the clothes assumed greater uniformity, abandoning the lavish fantasies of the previous years in the name of the rigor of the war. Even the hairstyles became more hurried, with hair pulled back and cut shorter. At the end of the war, fashion tried to restore a new elegance to working women, but without losing the practical character that clothes had taken over the last few years.

The end of the war led to a downsizing of armies and directed the industry towards products that meet the new demands of an exclusively civilian market. The jobs diminished and the first to be fired were women. Those who found themselves in the most difficult situation were the widows and wives of the invalids of war: for these the loss of an occupation represented a dramatic event because, in the absence of a husband who was able to work, succeed in supporting the family became particularly difficult.

In any case, for women a return to the pre-war situation was impossible because, at least in democratic countries, with the achievement of economic and political independence, they had found a new dimension in society from which it was no longer possible to go back.

ARTICOLO REDATTO DALLE ALLIEVE BAGNASCO , BAZZAN, BARBERA E QUARTO DELLA CLASSE V I DEL LICEO LINGUISTICO

During WWI (1914-1918), large numbers of women were recruited into jobs vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war. New jobs were also created as part of the war effort, for example in munitions factories. The high demand for weapons resulted in the munitions factories becoming the largest single employer of women during 1918.

Though there was initial resistance to hiring women for what was seen as ‘men’s work’, the introduction of conscription in 1916 made the need for women workers urgent. Around this time, the government began coordinating the employment of women through campaigns and recruitment drives. This led to women working in areas of work that were formerly reserved for men, for example as railway guards and ticket collectors, buses and tram conductors, postal workers, police, firefighters and as bank ‘tellers’ and clerks. Some women also worked heavy or precision machinery in engineering, led cart horses on farms, and worked in the civil service and factories. However, they received lower wages for doing the same work, and thus began some of the earliest demands for equal pay.

By 1917 munitions factories, which primarily employed women workers, produced 80% of the weapons and shells used by the British Army (Airth-Kindree, 1987). Known as ‘canaries’ because they had to handle TNT (the chemical compound trinitrotoluene that is used as an explosive agent in munitions) which caused their skin to turn yellow, these women risked their lives working with poisonous substances without adequate protective clothing or the required safety measures. Around 400 women died from overexposure to TNT during WWI.

Women’s employment rates increased during WWI, from 23.6% of the working age population in 1914 to between 37.7% and 46.7% in 1918 (Braybon 1989, p.49). It is difficult to get exact estimates because domestic workers were excluded from these figures and many women moved from domestic service into the jobs created due to the war effort. The employment of married women increased sharply – accounting for nearly 40% of all women workers by 1918 (Braybon, 1989: p. 49).

But because women were paid less than men, there was a worry that employers would continue to employ women in these jobs even when the men returned from the war. This did not happen; either the women were sacked to make way for the returning soldiers or women remained working alongside men but at lower wage rates. But even before the end of the war, many women refused to accept lower pay for what in most cases was the same work as had been done previously by men. The women workers on London buses and trams went on strike in 1918 to demand the same increase in pay (war bonus) as men. The strike spread to other towns in the South East and to the London Underground. This was the first equal pay strike in the UK which was initiated, led and ultimately won by women.

Following women’s demands for equal pay, a Committee was set up by the War Cabinet in 1917 to examine the question of women’s wages and released its final report after the war ended (Report of the War Cabinet Committee on Women in Industry, Cmd 135, 1919, p.2).

This report endorsed the principle of ‘equal pay for equal work’. But their expectation was that due to their ‘lesser strength and special health problems’, women’s ‘output’ would not be equal to that of men. Despite evidence that women had taken on what were considered men’s jobs and performed them effectively during the war, this did not shift popular (and government) perception that women would be less productive than men. The unions received guarantees that where women had fully replaced skilled men they would be paid the same as the men – ie would receive equal pay. But it was made clear that these changes were for the duration of the war only and would be reversed when the war ended and the soldiers came back.

On her first visit to Cradley Heath, the trade union agitator Mary Macarthur described the forges where the chains were made by women workers as akin to medieval torture chambers. While the average pay during that period was 26 shillings a week for men and 11s a week for women, the domestic chainmakers in Cradley Heath earned just 5s to 6s for a hard 54-hour week.

After a national campaign against low pay by the Anti-Sweating League, the government introduced legislation to end “sweating” in four trades, including the domestic chain trade, where a minimum wage of 11s 3d a week was set. The employers at Cradley Heath in the West Midlands refused to pay the new wage rate. In response, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW) called a meeting in August 1910 at which the women refused to work at the old rates. About 800 women workers began a strike, going on daily marches.

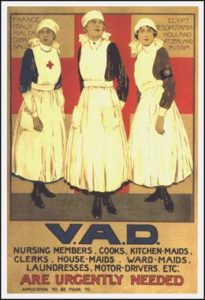

Poster for the Women’s Royal Air Force, detailing the need for Clerks, Waitresses, Cooks, Experienced Motor Cyclists and ‘in many other capacities’ Date: 1914-18

One immediate result of the war’s outbreak was the rise in female unemployment, especially among the servants, whose jobs were lost to the middle-classes’ wish to economise.

However, it was soon seen that the only option to replace the volunteers gone to the front was employing women in the jobs they had left behind; conscription only made this need even more urgent as had the Munitions of Work Act 1915 by which munitions factories had fallen under the sole control of the Government.

As the main historian of women’s work, Gail Braybon, claims, for many women the war was “a genuinely liberating experience” (link) that made them feel useful as citizens but that also gave them the freedom and the wages only men had enjoyed so far. Approximately 1,600,000 women joined the workforce between 1914 and 1918 in Government departments, public transport, the post office, as clerks in business, as land workers and in factories, especially in the dangerous munitions factories, which were employing 950,000 women by Armistice Day (as compared to 700,000 in Germany).

Women’s job mobility also increased enormously, with a large number of women abandoning service for factory work never to return to it to the chagrin of the middle-class women that were left without home help in many cases.

In general, women did very well, surprising men with their ability to undertake heavy work and with their efficiency. By the middle of the war they were already regarded as a force to be proud of, part of the glory of Britain. However, their entrance into the workforce was initially greeted with hostility for the usual sexist reasons and also because male workers worried that women’s willingness to work for lower wages would put them out of work.

The Government, besides, combined a welfare policy offering subsidies to families with husbands at the front with increasing female work in order to conscript skilled workers formerly regarded as indispensable to the war effort. To make up for the loss in the skilled workforce the entry of women in factories was often facilitated by ‘dilution’, that is to say, the breaking down of complex tasks into simpler activities that non-skilled women workers could easily carry out.

The women employed in munitions factories, popularly known as munitionettes have became the most visible face of the woman worker in WWI, though doubt remains as to whether their motivation was patriotic or simply economic. The factories they manned had been seized by Lloyd George’s Government and he also caused suspension of all trade union activities in them.

Munitionettes produced 80% of the weapons and shells used by the British Army and daily risked their lives working with poisonous substances without adequate protective clothing or the required safety measures. Although this can be seen as a gauge of their will to sacrifice everything for Britain it should be read, rather, as part of their treatment as cheap, easily replaceable labour.

The public recognition and sympathy that the ‘canaries’ (thus nicknamed for the yellow tinge that skin exposed to sulphur acquired) received could not make up for their work conditions. Leading trade-unionist Mary MacArthur, Secretary since 1903 of the Women’s Trade Union League, led an energetic campaign to demand they were paid as much as the men employed in the same industry – the women only got half the men’s wages – but by the end of the war the proportion was roughly still the same.

The Government also invited women to join the ranks of the Women’s Land Army, an organisation that offered cheap female labour to farmers not always keen to employ women. The 260,000 volunteers that made up the WLA were given little more than a uniform and orders to work hard as the fuel restrictions made a return to manual agricultural labour unavoidable; unless, that is, the Government used this as an excuse, counting on these women’s cheerful acceptance of any hardship to make working the land as cheap as possible.

It’s hard to say whether women workers understood from the beginning that their employment could only be temporary but so it was. The same situation was repeated in the main belligerent countries: women were dismissed back home to make room for the returning veterans, only in some cases their efforts were thanked with the right to vote. There are, besides, disagreements among historians, depending on whether they call themselves feminist or not, as to how much resentment this return home generated.

We must assume single women in families with no male casualties must have been more resentful than married women whose families had faced important loses or whose husbands had returned safely from the front. It’s important to remember at any rate, as Joanna Bourke does, that for women “Even more traumatic [than losing jobs] was the painful process of readjusting to the return of loved ones from the battlefields. Hundred of thousands of men returned from the war injured in some way. Women bore a large part of the burden of caring for these men. Even worse, women lost their fathers, husbands, lovers, brothers, and sons. For these women, life would never be the same.” Nor would it be for the men; they, however, needn’t fight for their right to have a job.

There is, therefore, a generalised consensus among historians that women were not truly emancipated by the Great War in any country involved in it. Ute Daniel explains in The War from Within: German Working-Class Women in the First World War that this was indeed the case for German women, noting that WWI’s most important outcome was shifting German factory women workers from one sector to another. She is quite critical that safety standards in factories fell back to 19th century standards and that women only acquired superficial skills as they were expected to be soon demobilised.

In Germany pronatalist policies together with an expanding welfare state focused on the family seem to have overruled the more pragmatic British and French approaches to using women in the war effort. Interestingly, Daniel points out that the German Government did not foresee how the scarcity of consumer goods – especially food – and the pressure this put on women would eventually create pockets of discontent that would undermine the women’s support for the war effort.

In Britain the gains were also modest, clashing not only with the upper and middle-class women’s desire to conquer a firm foothold in the professions but also with working women’s trade unionism. Leaders like Margaret Bonfield saw with dismay that the 1915 Board of Trade call for women to register at the Labour Exchange would work against the efforts of trade unions, saturating the job market with women happy to work for the lowest wages. She and Mary MacArthur tried to redress the situation asking that all women employed for war service became trade union members and that they got the same wages as men. They failed in both accounts.

As Gail Braybon and Penny Summerfield observe in Out of the Cage: Women’s Experiences in Two World Wars, (1987: 69), only women welders, tutored by the Women’s Service Bureau, managed to form during the war a compact, skilled, unionised group though this needn’t mean they did stay in their jobs. Joanna Burke adds that while by 1918 around 1,000,000 women were members of female trade unions, their wages did not significantly grow (Women and Employment on the Home Front During World War One, BBC) because of dilution: “By 1931, a working woman’s weekly wage had returned to the pre-war situation of being half the male rate in more industries.”

L’assenza di molti uomini chiamati a combattere contro l’esercito austro-ungarico provocò delle conseguenze molto pesanti a livello economico e sociale.

La gran parte dei nuclei famigliari erano di origine contadina, legati alle consuetudini e alle tradizioni di un tempo: i membri maschili avevano il compito di lavorare fuori dalle mura domestiche mentre le donne eseguivano le proprie mansioni all’interno, accudendo i figli e sbrigando le faccende di tutti i giorni. Le cose non erano molto diverse nemmeno per le famiglie “operaie” dove l’unica differenza era l’impiego degli uomini nelle fabbriche anziché nei campi.

Una situazione che mutò profondamente nel 1915. I posti di molti contadini ed operai furono lasciati vuoti e vennero coperti da chi era restato e non sarebbe mai stato chiamato al fronte: le donne. Si trattò di un momento molto importante per la storia sociale del Paese. Il loro ruolo, per la prima volta, passò da “angelo del focolare domestico” a membro attivo dell’economia e della società collettiva.

Non che le donne fossero del tutto nuove a questo tipo di esperienza: molte di loro erano già abituate a contribuire al lavoro nei campi mentre, a livello industriale, la loro presenza era già stata registrata nel settore tessile. Ma adesso il loro numero era aumentato considerevolmente e furono presenti in settori del tutto nuovi come la metallurgia (riconvertita alle esigenze belliche), la meccanica, i trasporti e mansioni di tipo amministrativo.

Ovviamente questo processo non fu indolore: non essendo state previste delle divisioni del lavoro, le donne erano obbligate a compiere gli stessi lavori dei colleghi maschi, anche quelli più pesanti. Nei campi era necessario spostare i covoni di fieno o i sacchi di grano, accudire il bestiame e utilizzare tutte le macchine agricole. Allo stesso modo all’interno delle fabbriche dovevano essere sollevati pesi non indifferenti e compiuti gesti ripetitivi e meccanici.

Le donne presero il posto dei propri mariti (o figli) anche in quelle faccende domestiche tipicamente maschili come le questioni burocratiche, gli acquisti o le vendite di prodotti agricoli ed i problemi di natura legale.

A questa sorta di “emancipazione” lavorativa non corrispose però una maggiore libertà a livello personale: nonostante l’assenza degli elementi maschili in età arruolabile, spesso nelle case rimanevano gli anziani i quali, come da tradizione, continuavano ad esercitare il loro ruolo autoritario all’interno della famiglia. Inoltre non mancavano diffidenze e gli atteggiamenti di rifiuto da parte dei moralisti e tradizionalisti: “Nelle fabbriche metalmeccaniche la presenza femminile era talvolta avvertita, specialmente dai vecchi operai, come un sovvertimento dell’ordine naturale e un attentato alla moralità.” (Antonio Gibelli, “La Grande Guerra degli Italiani”, BUR, Milano, 2009, p. 193). Un modo di pensare che peggiorò col tempo, quando le ragazze più giovani, sempre più spesso, si spostarono dalla loro casa per trovare un’occupazione.

In France, once war was declared and universal mobilization decreed, Prime Minister René Viviani instituted a poster campaign on August 2, 1914, targeting the women of the country’s farming families. In the expectation that the war would soon be over, at this time, it seemed to be enough to ensure that these women would take care of the only truly urgent need. The appeal read:

“Rise up, Frenchwomen, little children, sons and daughters of the fatherland! Take over the work of those who are on the battlefield. Be ready to show them tomorrow that the soil is plowed, the harvest is in, and the fields are sown. In this hour of need, no task is small. Everything that serves the country is great. Rise to action and toil! Tomorrow, there will be glory for everyone.”[1]

Women very quickly stepped up and moved into all the sectors of economic activity in all the countries engaged in the war, whether they offered their services as volunteers or not. They were considered, as in a further pronouncement by Viviani, a lynchpin in the struggle for victory. The men having left for the front, the women had to replace them in the fields, factories, and workshops to satisfy labour needs that had sharply increased in certain industries due to the war.

It is tempting to conclude, as several historians have done, that the role of women in the Great War constituted the first step on the path to emancipation. According to this interpretation, the image of the garçonne, a woman with short hair who has ripped off her corset and become independent, originated in this period, with the term itself being coined right after the Armistice.

However, the debate over the so-called emancipation of women in the Great War is more complex than it appears, and should be more closely examined to avoid facile generalizations and the construction of what Françoise Thébaud calls “a hagiographic image of feminine mobilization”[2] and the impression of a war that liberated women.

A COMPLEX HISTORIOGRAPHY

This subject, one of many in the field of First World War studies, intersects with a branch of historiography that is specifically focussed on the history of women and has evolved in the framework of gender history, as well as in social and cultural history in a broader sense. According to Françoise Thébaud, we can identify different eras in the development of this relatively recent historiographical tendency.[3] Initial studies, done at the end of the 1960s, mainly concerned the lives of professional women in wartime, and emphasized the changes wrought by the war in Great Britain. Historians at the Imperial War Museum spearheaded these studies, which concentrated on the activities of prominent Englishwomen, a source a national pride. A second tendency that appeared in the 1980s emphasized the conservative character of the war in the matter of gender relations. In the view of these scholars, either there was no female emancipation during the First World War, or if there had been, it was only temporary and superficial. In the 1990s, a third tendency underlined the importance of nuance, according to the scale of the object of study (individuals, groups, societies), the length of observation (results will differ in short-term, medium-term, and long-term studies), the approach, methods and tools used in studies, which have an influence on the type of sources consulted (social, cultural, judicial), and lastly, the different characteristics of the women (social class, age). Also during the 1990s, the reality of contemporary conflicts, particularly the war in the former Yugoslavia, completely overturned the idea that a war could be a terrain for female emancipation, bringing attention back to aspects that had been neglected in the research, such as rape and other atrocities specifically perpetrated upon women during war.

With these perspectives in mind, what is the truth about women’s roles in the First World War?

In Great Britain, more than one million women laboured in munitions factories during the war, and in Canada, out of a total population of eight million people, the number of the approximately 600,000 women who held permanent jobs at the beginning of the war doubled to 1,200,000 during the conflict. As the belligerent countries became more deeply involved in a war that promised to be much longer than first expected and therefore required the establishment of a true war economy, the female work force became absolutely indispensable. In countries where a high proportion of women worked before the war, such as France, they had most often carried out tasks that were considered secondary: “The women of the people had always worked. They were housewives, but they were also chambermaids, seamstresses, washerwomen, and street vendors. Later, with the expansion of the service sector, middle-class girls were given access to white collar jobs.”[5] What was new was the hiring of women, starting in 1915, in munitions factories, where they were quickly dubbed “bomb girls” or “munitionettes” (“obusettes” in France). At the height of the shell crisis and the war in the trenches, the number of female factory workers sharply increased, reaching 400,000 in France by the end of 1917, although the proportion of women hired varied considerably between companies: for example, between 60 percent of the shell-assemblers at Citroën were women, compared to the 20 percent working in arms and army vehicle manufacturing at Panhard-Levassor. At the beginning of 1918, when the mobilization of women appeared to have peaked, the total number of female workers in industry and commerce had risen above its prewar level by 20 percent.

French journalist Marcelle Capy, feminist and libertarian, worked incognito for several weeks in a munitions factory in wartime. Her account, published as a series in the magazine La Voix des femmes from November 1917 to January 1918, described the stressful work:

The worker, always standing, must take hold of the shell, place it on the machine, and lift off the top part of the device (the bell). Once in position, she lowers the bell and checks its dimensions, (…) lifts it up again, takes the shell and places it on the left. Each shell weighs 7 kilos. At the normal rate of production, 2,500 shells pass through her hands in 11 hours. As she has to lift each one twice, it means that she lifts 35,000 kilos every day. After three quarters of an hour at this job, I had to give up. I watched my comrade, young, docile, and frail in her big black apron, continue her work. She has been at this work station for a year. As 900,000 shells have passed through her fingers during this period, she has lifted seven million kilos at her job. Rosy-faced and robust when she started out, she has lost her lovely colour and is now a thin, exhausted girl. I look at her in amazement, and the words ‘thirty-five thousand kilos’ echo in my head.[7]

In recent historiography, the study of individual cases has revealed that the effects of the war were not the same for all women. Significant differences distinguished their destinies according to their ages and social conditions. Young women from middle-income and wealthy backgrounds, as well as orphans, seem to have improved their lots during the war, gaining in autonomy and independence. Also, as many of them worked in the service sector, their jobs were much less onerous. The First World War also conferred professional status to nursing[8] and feminized the services sector, with increasing numbers of young women and girls of the middle class finding employment in this sector, which had developed considerably since the Belle Époque of the turn of the century.[9]

However, once the war ended, the majority of women resumed their prewar activities, and in general, the respective societies seemed to want to return to the situation that existed before the conflict—in all domains, not just in those concerning women. This choice was particularly evident in political speeches and posters. It was even reported that “this development is not to the taste of soldiers, who fear a loss of their status once peace has returned.”[10] The men were expected to go back to work, and the women to resume their tasks of the past. However, a return to the “normal state of affairs” was impossible, due to the loss of so many active members of the population, particularly men, with approximately 9.7 million soldiers of all nationalities having been killed in combat.

FEMINISM DURING THE GREAT WAR

At the beginning of the 20th century, feminism had achieved undeniable success in Europe and North America, led by charismatic figures who fought for equal rights for women. In France, the most dynamic association dedicated to the franchise for women was the Union française pour le suffrage des femmes, headed by the strong-willed Marguerite de Witt-Schlumberger. Other courageous pioneers of the movement, such as psychiatrist Madeleine Pelletier, demanded the availability of contraception and abortion. However, on the whole, French feminism remained moderate and was limited to lobbying for civil rights, with a tendency to accept compromises.

From 1914 onward, in France, the majority of feminists supported the Union sacrée, the political truce between French political parties during the war, with Marguerite de Witt- Schlumberger calling upon women to follow this path. This “patriotic feminism” movement contributed to the war effort in several countries, providing solace to soldiers, tending to the wounded, and offering labour power and energy to the means of production. In general, it received support from the various governments through the application of measures to encourage women to work, although on the whole, this was done in a strongly conservative spirit.

The feminist struggle during the war essentially centered on demands for equal rights and equal salaries for women, especially as many of them worked in gruelling conditions for a pittance. Indeed, the slogan most often heard was “equal pay for equal work.” Women occasionally organized strikes, which led to raises in salaries, notably in the munitions factories where women risked their lives working with toxic materials at a dangerously fast pace.

The right to vote was the ongoing objective that united feminists from the start. However, numerous divergent tendencies among feminists caused splits within the movement. In France, feminists included patriots, neo-Malthusians like Nelly Roussel, who lobbied for the legalization of abortion, and socialists such as Hélène Brion, Madeleine Vernet, and Louise Saumoneau. In March 1915, this last activist participated in the third International Conference of Socialist Women in Bern, a gathering of feminist anti-war activists who had remained loyal to Internationalism.

In Great Britain, the suffragette movement, which had existed since 1865, took a more radical turn between 1903 and 1917. Emmeline Pankhurst, founder and leader of the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) from 1903 until her death in 1928, called for direct action to win the franchise for women, thus launching an important new wave of feminist militancy.

Arrest of Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst in Victoria Street, 13th February 1908

Since 1908, the suffragettes had effectively promoted their views in a newspaper, Votes for Women, that urged the women of London to demand the franchise. In 1910, Hyde Park was filled with thousands of supporters of the suffragettes, carrying banners bearing the slogan “Deeds Not Words.” Emmeline Pankhurst organized many demonstrations and provocative actions, in which she and other suffragettes carried out hunger strikes, chained themselves to lampposts, set fire to buildings, and cut telegraph wires, which caused her to be arrested five times between 1908 and 1913. When she was released from prison in 1914, she publicly supported the war effort and travelled to the United States to urge support for the Allied forces. She also called on women to volunteer as nurses during the conflict.

An example of radical feminist protest occurred in London on March 10, 1914, when Canadian suffragette Mary Richardson entered the National Gallery and slashed Diego Velázquez’s painting The Toilet of Venus (the Rokeby Venus) with a meat cleaver; she was subsequently sentenced to six months in prison. In a statement explaining her actions to the WSPU, she said the destruction of the image of the most beautiful woman in mythology was a protest against the government’s slow murder of Mrs. Pankhurst.

In 1917, the suffragettes’ intensified actions finally led to a debate in the British House of Commons on the vote for women, in which it was decided to give women over the age of 30 the right to vote in the December 1918 parliamentary elections. Inspired by this positive development, women in other parts of the British Commonwealth began their own struggles for the franchise.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Montreal was a hub of feminist activity in Canada. A mainly anglophone association, the Montreal Local Council of Women, founded in 1893, had its French-language equivalent in the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste, created in 1907. Like their European counterparts, these organizations campaigned for the recognition of women’s political and legal rights, as well as for access for women to institutes of higher learning and to the liberal professions. Marie Gérin-Lajoie (1867–1945) and Julia Drummond (1897–1937) were among several Montreal women, mostly of the upper-middle class, who stood out in this phase of the struggle for women’s rights in Canada.

When the First World War ended, feminists expressed their desire to participate in the peace negotiations, in vain. The postwar public discourse in France—not surprisingly, as it was dominated by men—treated the women’s movement largely as a bourgeois struggle. Added to this was the idea that women’s rights should not be a central issue at a time when, after four years of devastating war, the major concern was the depleted population and the efforts to solve this problem. In January 1919, when women were officially demobilized by the authorities, the difficulty lay in providing assistance to the world’s four millions war widows, of whom almost 700,000 lived in France. Attempts to achieve women’s emancipation were relegated to narrow circles of bourgeois intellectuals. For the majority of women, the postwar period was characterized by a return to normality, i.e., the status quo. In France, a country traumatized by the loss of so many lives, women were expected to resume their roles as wives, homemakers, and mothers—especially if their children had lost their father—and natalist policies were promoted.[11] The French parliament even passed a law, which, by repressing birth control practices, pressured Frenchwomen to conceive and repopulate the country after the demographic catastrophe that was the Great War.

Ultimately, in France, none of the changes demanded by feminists were achieved at the end of the war, or even in the 1920s. Women did not obtain the franchise, nor did they see an improvement in their legal status as married women. In 1919, the French Chamber of Deputies did vote in political rights for women, but the Senate, dominated by members of the Radical Party who were fearful of giving the franchise to women, blocked the bill. They thought women would follow their local priests and confessors in voting preferences, and therefore, that France would become even more conservative. German women, on the other hand, obtained full voting rights at the end of the war. In other countries, such as Canada, the female franchise was granted to certain categories of women in 1917 and was extended, for federal elections, to women who were British subjects aged 21 and up, and who “possessed the qualities that would allow a man to vote.” In Belgium, according to a law of 1921, the franchise for all elections was granted to war widows, while other women could vote only on the municipal level.

FEMALE SPIES: AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

On the role of female spies during the First World War, see the full version of the article by Chantal Antier, “Espionnage et espionnes de la Grande Guerre”Revue historique des armées, No. 247, “Dossier Le renseignement”, 2007, pp. 42–51.

CONCLUSION

All things considered, the First World War, far from being a time of true emancipation for women, was a time of trials for them, just as it was for the men. The war brought everyone his or her share of suffering. That of the women in the belligerent countries was caused by separation from loved ones or grieving for them, and for having to take on all the family tasks and responsibilities, including the provision of food, in a context of hardship and shortages of all kinds. Moreover, the crimes and abuses committed during the months of invasion and the years of occupation on the Western Front (northern France and Belgium) essentially affected women, who were directly confronted with the experience of war. They faced rape, forced labour, and deportation, whether they were in zones already occupied by the enemy or whether they were accused of resisting the enemy during the invasion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY / WEBOGRAPHY

- 14–18. Le magazine de la Grande Guerre, No. 1, April-May, 2001.

- Antier, Chantal, “Espionnage et espionnes de la Grande Guerre,”Revue historique des armées, No. 247, “Dossier Le renseignement,” 2007, pp. 42-51.

- Ripa, Yannick, “Aux femmes la patrie peu reconnaissante,” L’Histoire, No. 61: 14–18. La catastrophe, October 2013.

- Thébaud, Françoise, “Penser la guerre à partir des femmes et du genre: l’exemple de la Grande Guerre,” Astérion (electronic journal), No. 2, “Dossier Barbarisation et humanisation de la guerre,” ENS Éditions, 2004.

- Thébaud, Françoise, “Femmes et genre dans la guerre,” in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Jean-Jacques Becker (ed.), Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, Montrouge (92), Bayard, 2004, pp. 613-625 (centenary edition, 2014, reprinted by Perrin, coll. “Tempus,” 2012).

- Thébaud, Françoise, “La guerre, et après,” in Évelyne Morin-Rotureau (ed.), 1914–1918: combats de femmes, Paris: Autrement/Ministère de la Défense, 2004, pp. 185-199.

- “Les femmes et la Première Guerre mondiale” in the Réseau Canopé website.

Commenti recenti